If you are viewing this from facebook, please visit the original article, for better formatting.

Ontological arguments are fun, aren’t they? I’ve had this one on the back burner for a while now1, and I had hoped to make some improvements before discussing it with anybody. However, last night after finishing up an article on Levinas by Roger Burggraeve 2, I came to all-too-many realizations which should have been obvious to me long ago. One of these realizations is that my ideas will not improve substantially if they are not subjected to the unexpected (i.e. the perspectives of Others).

I should begin by mentioning a few caveats:

- This is an argument, not a proof

- The product of the argument is not the stereotypical Christian God, nor any other well-defined God with knowable attributes. In fact, it is a more vague God than even that abstracted object of Anselm’s famous argument3.

My argument is something done for my own pleasure and as an example of my method of applying philosophical categories. One of my long-standing criticisms of most philosophers and most philosophies, is that they tend to proffer, promote, and perpetuate false dichotomies and sets of categories which hold some of these qualities:

- Categories or alternatives are presented as binary opposites, when they are not. In fact, I would argue that in most of these cases, so-called binary opposites are not even mutually exclusive.

- Likewise, categories are presented as distinct when they are not necessarily so.

- Categories, distinctions, or divisions are presented as the only available or important options, when in fact the only “only” which these categories have in common is that they were the only categories or distinctions that the philosopher could think of at the time.

- Categories distinguish quantities or qualities based on the assumption that these can be meted out discretely, when in fact it is not clear that they can be.

Note that one mode of categorization that I am explicitly ruling out here, is the classic binary 2×2 table. I don’t think, in other words, that our perceptions, experience, and reason give us enough information to presuppose that, for example, a thing must either be or not be, a thing must either be good or not be good, a thing must either be one thing or many things4

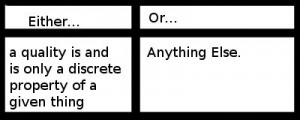

In response to this, I have tried to think up some sort of system of categories which can be applied to the real world, and the only categorization I have been able to think up5 is the following, presented in a nice6, discrete table:

Note: Please forgive my imprecise/confusing language; I have no real experience yet in formal logic.

Now, this little categorization is fun, because it allows me to get away with a lot. The “anything else” category includes such gems of possibility as: 1) the given quality is extant, 2) the given quality is both extant and not extant, 3) the given quality is somehow neither extant nor not-extant, , 4) the artificially abstracted categorical quality is not itself measurable, identifiable, abstract-ible, describable, or is otherwise irrelevant, or–my favorite–5) anything else.

The Argument for God’s Existence!

Just for fun, I’ll apply my categorization method to God’s existence. Take the following possibilities:

- solipsism: either you and only you exist, in a discretely definable way, or…

- anything else

I suspect I have already gotten you, by this point, to agree to the equation, and, in most cases, to believe that option #1 is false7. Now comes the controversial part of the argument–the definition of God. My challenge here is to find a way to get you to accept “anything else” as implying God. A slight reformulation might help get my point across before I go any further. Take, now, these possibilities:

- solipsism: either you know/perceive, all that there is to be known/perceived8

- anything else

A tempting route to go from here is to say “if I do not perceive/know everything that can be known/perceived, what exists which can be, counterfactually, perceived?”, or, in other words, “what is the source of my knowledge?”. Hopefully there are a few romantic transcendentalists out there who are willing to let me apply Ralph Waldo Emerson’s definition of God/Nature here: the vague not-me9. Of course, this assumes a source is required and that it is the excess of knowledge that makes is disagree with proposition #1. There is no need, however, to presume any discrete division between a me and a not-me. It might also be the case, that neither I nor knowledge/perception are discrete in such a way as to fit into the restrictive bounds of option #1. This is fine, because the fluidity of self-identity jibes well with other definitions of God, such as Spinoza’s great pantheist notion, certain Buddhist and shamanistic approaches, and the like. Phenomenologists among us will point out that all we need is an Other to demonstrate against proposition #1, and the Other need not be God. I am rather content, though, to let this Other stand retain the same role as Emerson’s not-me, such that the Other, or indeed an aggregate of others, fulfills the minimum role of God, should no other discrete being be evident.

Okay, whatever…

Alright, perhaps I did not quite get to the grand argument for God’s existence. What did I learn in the process? While I have appreciated attempts to give philosophical systems some sort of reasoned foundation, it seems all of these attempts rely on assumptions which do not necessarily hold. In attempting my own such system, I found really, only one small means of sorting out knowledge which I have been unable to disprove as a tool (my either/or tool used and explained above). Unfortnuately, this tool, as applied, typically only allows me to say only “okay…so…’anything else’ is the reality”. In other words, I have found that the strictest standards of scrutiny have shown me that, if we want to say anything, we have to start making precarious generalizations, inadequate analogies, erroneous abstractions, and arbitrary categorizations at some point, if we want to be able to say anything interesting or useful. Hopefully, time and energy will and has allowed us to demonstrate (with faith in probability as a founding assumption, unfortunately) which of the unprovable tools of logic, perception, and knowledge-making (modus ponens, modus tollens, statistics, calculus, analogies, etc.) give us results that are more true, more often (or at least more beneficial). Still, I hope my categorization example has gotten someone out there to ponder, in some useful way, the similarity between believing in any not-me and beliving in God. I do love feedback, if for anyone who has managed to get through this wordy writing. If you have any rule of logic that you think might survive my scrutiny, I would love to hear about it!

- since I read Sartre’s Being and Nothingness—L’Être et le néant, over a year ago ↩

- The Bible Gives to Thought: Levinas on the Possibility and Proper Nature of Biblical Thinking, from Jeffrey Bloechl’s The Face of the Other and the Trace of God ↩

- Broken down in a fun way here ↩

- I suspect many, perhaps most, intelligent people will argue against me on all of these points on a case-by-case basis. Some categories, like number or existence to mention some off-the-cuff, seem to be discrete. In other words, I suspect most people would probably say that we can know that, for example, a thing either exists or it does not exist. Or, one might argue, one must be able to describe (as a numeric category) the quantity of a thing. To the contrary, my suspicion is that we terms like existence and number express a kind of practical convenience in language, and though it may be difficult to imagine how a thing might partially exist or both exist and not-exist, that does not mean these categories can be ignored. I should love to argue this point with any takers, though, as I am willing to admit that it is hard to come up with clarifications and examples for this sort of provisional thinking. ↩

- Warning! Warning! Flags should be going up right now if you have been awake while reading this! ↩

- yes, “precise”, for you philologists! ↩

- I would love to argue about this one, too. ↩

- While most people–even some supposed solipsists–will deny this outright, I think this theory warrants more merit than we generally give it. Our experience has conditioned us to believe that intellectual solipsism is false on its face, but if infant psychology has anything to say about this, the assumption was not once so well ingrained. Imagine the infant who thinks that when mommy disappears mommy no longer exists and is marvels at when some object appears to have a back side. ↩

- See Nature ↩